- Home

- Nicole Chung

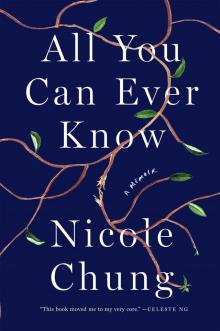

All You Can Ever Know

All You Can Ever Know Read online

The author has tried to re-create events, locales, and conversations based on her own memories and those of others. In some instances, in order to maintain their anonymity, certain names, characteristics, and locations have been changed.

Copyright © 2018 by Nicole Chung

First published in the United States in 2018 by Catapult (catapult.co)

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-1-936787-97-5

eISBN: 978-1-936787-98-2

Catapult titles are distributed to the trade by Publishers Group West

Phone: 866-400-5351

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018938840

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for Cindy

and for our daughters

. . . I wanted to know,

whoever I was, I was

—MARY OLIVER, “Dogfish”

What? You too? I thought I was the only one.

—C. S. LEWIS, The Four Loves

Part I

The story my mother told me about them was always the same.

Your birth parents had just moved here from Korea. They thought they wouldn’t be able to give you the life you deserved.

It’s the first story I can recall, one that would shape a hundred others once I was old enough and brave enough to go looking.

When I was still young—three or four, I’ve been told—I would crawl into my mother’s lap before asking to hear it. Her arms would have encircled me, solid and strong where I was slight, pale and freckled against my light brown skin. Sometimes, in these half-imagined memories, I picture her in the dress she wore in our only family portrait from this era, lilac with flutter sleeves—an oddly delicate choice for my solid and sensible mother. At that age, a shiny black bowl cut and bangs would have framed my face, a stark contrast to the reddish-brown perm my mother had when I was young; I was no doubt growing out of toddler cuteness by then. But my mom thought I was beautiful. When you think of someone as your gift from God, maybe you can never see them as anything else.

How could they give me up?

I must have asked her this question a hundred times, and my mother never wavered in her response. Years later I would wonder whether someone told her how to comfort me—if she read the advice in a book, or heard it from the adoption agency—or if, as my parent, she simply knew what she ought to say. What I wanted to hear.

The doctors told them you would struggle all your life. Your birth parents were very sad they couldn’t keep you, but they thought adoption was the best thing for you.

Even as a child, I knew my line, too.

They were right, Mom.

By the time I was five or six years old, I had heard the tale of my loving, selfless birth parents so many times I could recite it myself. I collected every fact I could, hoarding the sparse and faded glimpses into my past like bright, favorite toys. This may be all you can ever know, I was told. It wasn’t a joyful story through and through, but it was their story, and mine, too. The only thing we had ever shared. And as my adoptive parents saw it, the story could have ended no other way.

So when people asked about my family, my features, the fate I’d been dealt, maybe it isn’t surprising how I answered—first in a childish, cheerful chirrup, later in the lecturing tone of one obliged to educate. I strove to be calm and direct, never giving anything away in my voice, never changing the details. Offering the story I’d learned so early was, I thought, one way to gain acceptance. It was both the excuse for how I looked, and a way of asking pardon for it.

Looking back, of course I can make out the gaps; the places where my mother and father must have made their own guesses; the pauses where harder questions could have followed: Why didn’t they ask for help? What if they had changed their minds? Would you have adopted me if you’d been able to have a child of your own?

Family lore given to us as children has such hold over us, such staying power. It can form the bedrock of another kind of faith, one to rival any religion, informing our beliefs about ourselves, and our families, and our place in the world. When tiny, traitorous doubts arose, when I felt lost or alone or confused about all the things I couldn’t know, I told myself that something as noble as my birth parents’ sacrifice demanded my trust. My loyalty.

They thought adoption was the best thing for you.

Above all, it was a legend formed and told and told again because my parents wanted me to believe that my birth family had loved me from the start; that my parents, in turn, were meant to adopt me; and that the story unfolded as it should have. This was the foundation on which they built our family. As I grew, I too staked my identity on it. The story, a lifeline cast when I was too young for deeper questions, continued to bring me comfort. Years later, grown up and expecting a child of my own, I would search for my birth family still wanting to believe in it.

One afternoon in the summer of 2003, two people I had just met sat across from me in their sunny apartment and asked if I thought they should adopt. They had tried for a few years and been unable to conceive; now they wanted to adopt a child from another country. They named some programs they were interested in. None would lead to them bringing home a white child.

They asked if I ever felt like my adoptive parents weren’t my “real” parents.

Never, I said firmly.

They asked if I had been in touch with my birth family.

No, I said, I hadn’t.

They asked if there had ever been any issues when I was growing up.

I felt something like panic, the sudden shame of being found out.

Perhaps confusion was all they could read on my face, because one of them attempted to clarify: Had I ever minded it? Not being white, like my parents?

I wanted to answer. I liked this couple, and I knew it was my job to offer them the comfort, the encouragement they so plainly deserved. Did I mind not being white? It amounted to asking if I minded being Korean; yes, I minded, or no, I didn’t mind, both seemed too mild for how I’d felt.

The truth was that being Korean and being adopted were things I had loved and hated in equal measure. Growing up, I was the only Korean most of my friends and family knew, the only Korean I knew. Sometimes the adoption—the abandonment, as I could not help but think of it when I was very young—upset me more; sometimes my differences did; but mostly, it was both at once, race and adoption, linked parts of my identity that set me apart from everyone else in my orbit. I could neither change nor deny these facts, so I worked to reconcile myself to them. To tamp down the stirring of anger or confusion when that proved impossible, time and time again.

All members of a family have their own ways of defining the others. All parents have ways of saying things about their children as if they are indisputable facts, even when the children don’t believe them to be true at all. It’s why so many of us sometimes feel alone or unseen, despite the real love we have for our families and they for us. In childhood, I was uncertain who I was supposed to be, even as I resisted some of my adoptive relatives’ interpretations—both you’re our Asian Princess! and of course we don’t think of you as Asian. I believe my adoptive family, for the most part, wanted to ignore the fact that I was the product of people from the other side of the world, unknown foreigners turned Americans. To them, I was not the daughter of these immigrants at all: by adopting me, my parents had made me one of them.

And perhaps I never would have felt differently—perhaps I, too, would have thought of myself as almost white—but for all the people who never indulged this fantasy beyond my home, my family, the reach of my parents’ eyes. Caught between my family’s “colorblind” ideal and the obvious notice of othe

rs, perhaps it isn’t surprising which made me feel safer—which I preferred, and tried to adopt as my own.

Somewhere along the way, though, after leaving home, I had learned to feel strangely proud of my heritage. I’d made friends in middle school and high school who liked and accepted me even though I was one of the few Asian kids they knew. Then I had gone off to college and found myself living among huge numbers of fellow Asians; on campus, which soon felt more like home than the town where I had lived all my life, I finally learned how it felt to exist in a space, walk into a classroom, and not be stared at. I loved being just one Asian girl among thousands. Every day, I felt relieved to have found a life where I was no longer surrounded by white people who had no idea what to make of me.

Still, I did not know what it meant to be a Korean completely sundered from her culture, or if I could truly call myself a Korean at all—when my Korean American dormmate in college referred to me as a “banana,” I knew enough to understand it was not a compliment, but had no real defense. To me Korea was little more than a faraway country, less real to me than a fantasy, and my own Korean family existed in an alternate timeline I could hardly begin to imagine. I had yet to grapple with or resolve my adoption’s place in my life, what it meant and how I ought to think of it—at twenty-two, sitting in my new friends’ dining room, a genuine, perhaps more generous understanding of who I was still flickered beyond my reach.

I looked from one pair of earnest eyes to the other, wondering how I could explain all this to them. How had I gotten here? How had I become the voice of reassurance for two people about to embark on parenthood? I’d been out of college a matter of weeks. I still had trouble thinking of myself as an adult. I had no idea what it took to raise a child, let alone one whose face would announce to everyone that they weren’t born into their family.

My hometown is a five-hour drive from Portland, nestled in a valley in sight of three mountain ranges. For years now, when I go home, it has been my ritual to step off the plane and begin counting the people of color in the town’s one-room airport; often, there’s only me. I spent eighteen years there without getting to know another Korean.

Once my parents and I left our little house on Alma Drive, we were bound to turn heads. Where did they get you? people at the grocery store asked. Or, on the playground, How much did you cost? Kids at school wanted to know why I didn’t look like them. Teachers stumbled over my Hungarian surname, looking perplexed even after my corrections.

To my family’s credit, my adoption was never kept secret from me—not that it could have been, I suppose. I avoided the fate of adopted children of earlier generations, who were often told about their adoptions late in adolescence, as adults, or not at all. An adopted woman I met once told me she didn’t learn she was adopted until she was a teenager, an echo of other stories I’d heard before. She found out by accident; friends and relatives knew, and one day someone let slip the neighborhood secret.

My parents explained my adoption when I was too young to remember, adding details over the years until I knew almost everything they did. Just as I don’t remember the day I learned I was adopted, I don’t remember precisely when I realized I was practically the only Asian I ever saw—but I imagine it must have been sometime in kindergarten, my first year of school. I was already aware that no one in my family looked like me—nor did anyone in our neighborhood, or in my grandmother’s neighborhood across town—but it hadn’t mattered much in the years before I stepped through the doors of our town’s only Catholic school, because I knew so little about people beyond the circle of my own family.

There were around twenty-five kids in my afternoon kindergarten class, every one of them white. At morning circle, on the playground, packed into the pews during school-wide Masses, at assemblies and concerts and sporting events, it was the same: white child after white parent, face after face that looked nothing like mine. By the age of five, I must have had words like Korean and Asian to describe myself, because I remember deploying such terms at school. I might have also possessed a vague, sight-based understanding of whiteness. But having never talked about race with anyone before, I couldn’t have strung together the words to describe what I was seeing—or not seeing—just as I couldn’t have told anyone why it suddenly mattered.

And at first, in truth, it wasn’t so difficult to be the only Asian girl in my class. A particularly innocent classmate once asked me, “Are you black?” and this was easily answered. One of so many towheaded girls said, “Mary did not have black hair!” when the Christmas pageant rolled around, and I decided that was fine, because the angels got wings and better songs. I knew I was different, but during kindergarten I believed it was simply a fact, one that caused me little distress.

In first grade, when I took my turn as the designated “Very Important Person,” I brought in my family photos glued to white poster board as all the kids before me had. My classmates, arranged in a semicircle on the woven rug, naturally wanted to know why all of my pictures showed me flanked by my redheaded, freckled white mom and early-graying white dad, though that wasn’t what they said—what they said was, “Are those your parents? How come you don’t look like them?” I spent most of my presentation explaining matters, but I didn’t mind much; it was thrilling, in a way, to hold so many of my classmates in thrall. A strange feeling spiked, the earliest suspicion that I might eventually spend a great deal of time answering people’s questions about adoption, but I told myself it was fine. How lucky that I already knew so much about it.

Then one of my classmates thrust his hand in the air. His face was expectant—and a little reproachful, as though I’d stopped reading just before the end of a rollicking good story and was deliberately keeping everyone in suspense. “Don’t you want to meet your real parents?”

No one in my family ever referred to my birth parents as my real parents. But once I got over my initial shock, I understood why he had asked. Of course the other kids would be curious about my birth family. Of course they would want to solve the mystery I, too, obsessed over.

In the years to come I would hear variations on this same question, over and over, and it would never again surprise me—I just never knew what to say. What did it matter what I wanted? I wasn’t going to meet them.

When it was time to gather up my poster and return to my seat, I was glad I’d had the opportunity to tell my story. I could still tell myself that the unknown or confusing aspects of my history didn’t matter; that none of my classmates really cared that I was Korean, or that my family wasn’t like theirs. It was the last year I would be able to pretend that was true.

Facing the hopeful couple across from me, I knew I had to speak. We had been introduced by mutual friends precisely so I could tell them how wonderful it was to grow up adopted. “I just think it would be great for them to talk to you,” my friend had told me when she set up the meeting. I was there—I had agreed to go!—to offer reassuring statements about being raised by white parents who loved me. I wanted to be helpful. Why was I hesitating?

Ten, even five years earlier, it would have posed no great challenge; I’d never shied away from the story I grew up hearing. By the time a friend in middle school asked me what it was like to be adopted—as if I could compare it to anything else—I knew just how to laugh, just what to say. Most people are stuck with their kids, I told her, rather insufferably. My parents chose me. But I was out of practice, having spent the past four years at a university whose enrollment was one-quarter Asian. Friends and classmates and professors who had never seen me with my parents had little reason to ask if I was adopted. And when I did mention it now, when I told people like my college roommate or my faculty advisor or even my boyfriend, Dan, the fact emerged as a biographical footnote: people usually nodded and filed the information away, even if I did sometimes see curiosity spark in their eyes. My two worlds were three thousand miles and a world of experience apart, and rarely collided.

When Dan met my parents, in October

of my junior year, I was so anxious—I remember being irrationally convinced that he wouldn’t be able to understand or find common ground with them, generous and kind as he was. When he asked me why, I could only come up with one answer: We’re just so different. The old self-consciousness, the archetypically adolescent God, you guys are so embarrassing familiar to any teenager, had given way to the less cringing but still sure knowledge that my parents and I were opposites in every conceivable way, from how we looked to the ways our minds worked. They tended to act less like my parents and more like my peers; they were always telling me I worked too much, thought too much, cared too much. We weren’t really prepared to have a kid like you, my mother had said once, something she might have regretted if she were in the habit of questioning her words.

Even without this revelation, though, I would have known. I had always felt like the much-adored but still obvious alien in the family. I knew we didn’t always make sense to other people. And of course my adoption, the obvious explanation for it, was right there, but I could never bring myself to reference it—not even to Dan. It felt petty and wrong, like I was assigning blame to something I was supposed to be grateful for. I still wanted our family to pass muster as “normal,” whatever that meant, and so our differences—and how I came to belong to my parents—were not supposed to matter. Not to anyone we met, and certainly not to me.

Now, facing Did you mind it? from people I liked, people who wanted to become parents just like mine had, I was not yet thinking of their future child; I wanted to reassure them. I could see compassion and silent encouragement in their eyes, the promise of friendship, a churning worry they couldn’t entirely hide. Something about them tripped every quiet doubt, every fiercely protective instinct I’d ever had about my own family. Here were two potential parents who were ready to believe in adoption and so, by extension, the goodness and rightness of my own upbringing. How could I explain what it had been like? How my presence in my family, and especially in the town where I grew up, had often made so little sense to me? How could I tell them that their child might feel the same way, no matter how much they were loved?

All You Can Ever Know

All You Can Ever Know